Singapore is leading the way in abolishing some school exam rankings, stating that 'learning is not competition'. So how do we work out what we value if we no longer value exam results? We think we have the answer...

Where do you go when you’re at the top? That’s a question that might have gone through the mind of Ong Ye Kung, Singapore’s education minister, when he announced the end of ranking children by test scores.

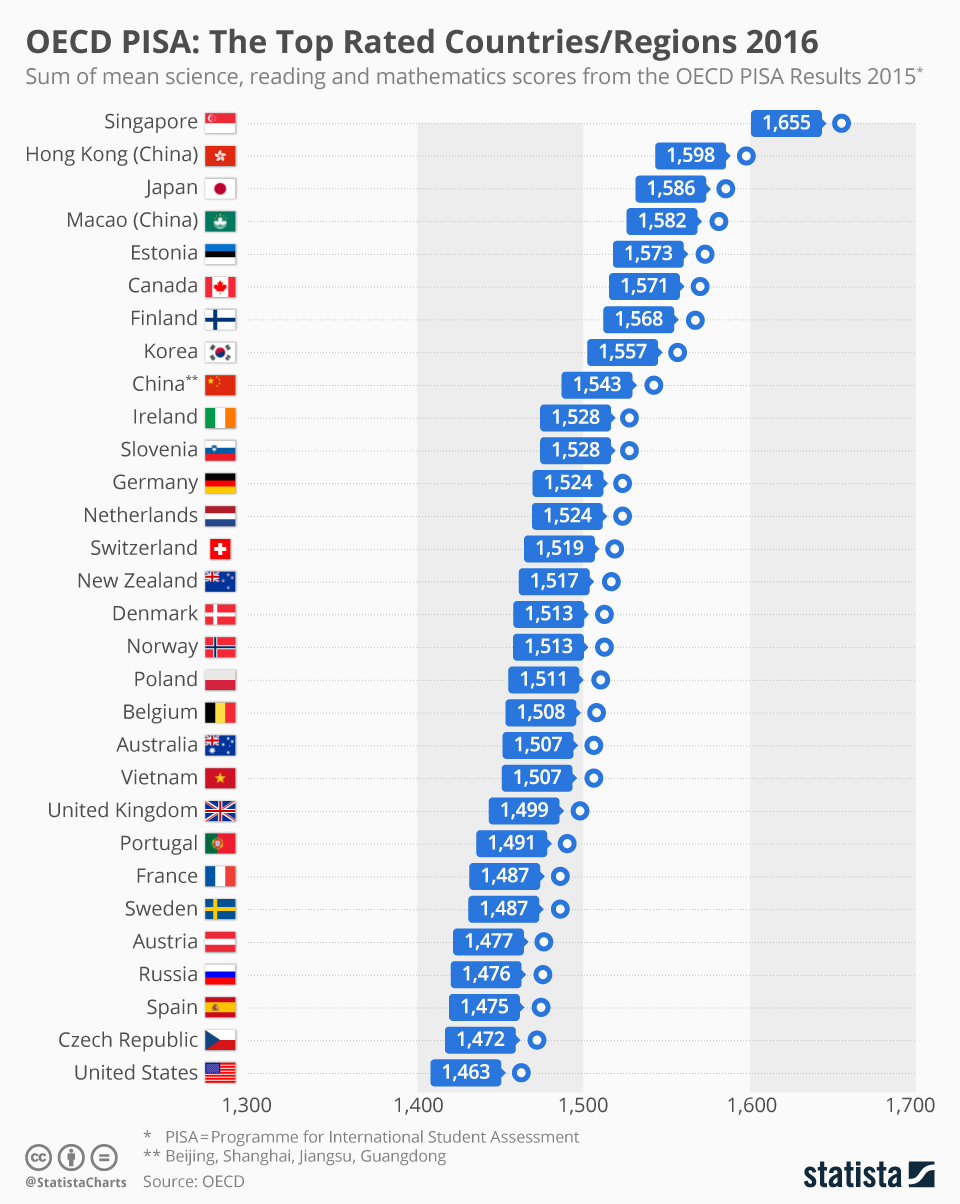

Singapore remember, currently sits at the top of the PISA global education rankings and is lauded by many other countries as an example of 'how to do it'. In fact, it's so far out in front, OECD education director Andreas Schleicher declared Singapore was "not only doing well but getting further ahead” when the tests were last carried out in 2016.

So changing tack when you’re the leader of the pack makes the Singaporean Government’s decision all the more interesting. They have come to realise that although exams, league tables, and rigid assessment might give your country a global pole position, it doesn’t give your country's learners the skills they need to be engaged, productive and happy citizens in the 21st Century.

As this World Economic Forum article states, 'shifting the focus away from exam perfection towards creating more rounded individuals represents a serious change of direction for Singapore. Alongside academic performance, the new policies aim to foster social development among pupils to raise self-awareness and build decision-making skills.’

So, instead of exam assessment, teachers will gather information about pupils’ learning through discussions, homework, and quizzes. Schools will use other ways like 'qualitative descriptors', in place of marks and grades, to evaluate pupils’ progress. Other institutions are already following suit, with the The Mohammed bin Rashid School of Government in Dubai having dropped exams to instead focus on 'the real world'.

Finally then, the penny drops. It’s a first step, but an important one, and given that it comes from a country at the top of the table, rather than at the bottom (USA) or the middle (UK), it’s a decision that should carry some weight in reducing our addiction to ranking.

Winners and losers in league tables

From Sunday league football to global GDP, seemingly everything is now ranked in charts, lists, and league tables and sadly, education is no exception. But can you really test, assess and rank a child’s education? Can you put a number on learning? Can you distil it down to a percentage?

Some think you can because their business model is based on it; we’re looking at you Pearson. They believe that if they could just find that magic teaching formula, then we can somehow crack education for good and automate and digitise the whole process with AI fed by huge amounts of data.

Teaching to the test isn’t new

When metrics become the coin of the realm, to refuse to use them is to risk bankruptcy

But how did our global education systems get in this mess? In his book, The Tyranny of Metrics, historian Jerry Muller explores how our addiction to educational measurement, assessment, and data collecting began. The story begins in England, in 1862, when MP Robert Lowe drives a law through parliament that schools would be funded based on their 'performance'.

The Government would test pupils’ reading, writing, and arithmetic (the famous three R’s) and award funding accordingly. Those that got the most questions right got more money, those that didn’t, well… You can clearly see the problem with this, as rather than encouraging a love of learning or creativity, teachers were financially incentivised to teach to the test.

Indeed, rallying against this approach was one of the Government’s own inspectors, the cultural critic and poet Matthew Arnold, who said in his book, The Twice-Revised Code,

“[In preparation for these tests] the teacher is led to think…not about teaching their subject but about managing to meet targets. They limit their subject as much as they can and within these limits try to cram their pupils… the ridiculous results obtained by teaching under these conditions can be imagined.”

That sentence could have been written an hour ago, rather than 156 years ago. Arnold frequently found himself in schools where pupils had ingested and could regurgitate mountains of facts but were completely devoid of any analytical skills.

In the 20th century, this process was developed further by the likes of mechanical engineer Fredrick Winslow Taylor, into the discipline of 'scientific management'. Here, every action from teaching to manufacturing could be measured, tabulated and assigned a value. Crucially, tasks perceived to have been performed optimally (i.e in the quickest time) were financially incentivised in the form of extra funding or overtime pay.

Todd Rose writes on this idea of speed in his book The End of Average, stating, "we have created an educational system that is profoundly unfair, one that favours those students who happen to be fast, while penalising students who are just as smart yet learn at a slower pace.”

Who inspects the inspectors?

And so we come full circle to today, where children's and teacher's abilities are considered as data sets to be managed by quangos and semi-autonomous Governmental bodies.

Here in the UK, specifically England and Wales, we have Ofsted, whose remit is to assess and grade teachers and schools, examine their performance, and deliver a score. The start of the 2018 academic year saw Ofsted repeatedly blotting its copybook.

First came the ‘must try harder’ report on them from the House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts, which stated ‘there have been clear shortcomings in Ofsted’s performance and if the level of inspection continues to be eroded, there is a risk that Ofsted will come to be perceived by parents, Parliament and taxpayers as not relevant or worse, simply a fig leaf for Government failures on school standards. Should this happen, its credibility will evaporate.’ (you can read the full report here).

That's a pretty strong statement. Furthermore, that credibility is underpinned by a system of measurement and assessment. But the ground is shaking.

Days later, HM Chief Inspector Amanda Spielman admitted that the organisation she leads adds to the 'teach-to-the-test’ mentality, where too much focus is put on exams and testing, with little regard for project-based learning or other ways to measure student development, comprehension, and understanding.

In October, Speilman sought to move the story on by announcing a new inspection framework in how it assess a school’s performance. In her Damascene conversion letter, she states:-

“We all have to ask ourselves how we have created a situation where second-guessing the test can trump the pursuit of real, deep knowledge and understanding of subjects.”

And she goes on; “for a long time, our inspections have looked hardest at outcomes, placing too much weight on test and exam results when we consider the overall effectiveness of schools. This has increased the pressure on school leaders, teachers and pupils alike to deliver test scores above all else.”

This has all happened on her watch. Speilman and her equivalents in other countries of the world stand at a crossroads, but as US writer and politician Upton Sinclair once said, ‘it is difficult to get a person to understand something when their salary depends upon them not understanding it.’

So what will we value?

But let’s assume for a moment that the winds of change are blowing. Let's assume that after 160 years we can somehow wean ourselves off the teat of the test and onto the solid food of experience-based learning driven by people's interests and passions. What do we value then?

Well, various studies and research from across the political spectrum highlight that the very skills we need to meet the imminent challenges of the future are skills such as creative thinking, critical analysis, collaboration across disciplines and deep emotional intelligence. These are what we should value.

But back to where we began. In this wide-ranging interview Dr. Lim Lai Cheng, director of SMU Academy at Singapore Management University sums up her country's new approach to education;

let’s help students find their passion and get a sense of personal mastery as they progress through the education system.

There is a reason as to why this is important that extends way out past a student's school years. It's to instil a sense of curiosity, self-worth, and learning that persists.

With robots, automation and AI already replacing lots of low skilled repetitive jobs, the opportunity here is to find new subjects, services and roles to explore, and yes, they are there and there can be enough for everyone. But to invent those, we need to be happy, creative and be able to build good relationships (all things robots are really bad at!).

In the end, what matters isn't so much the place you went to school or the job you have, but your relationships with other people. And yet nothing in our education systems addresses that in a meaningful way. Singapore's sense of national identity born from its short history and geographical location has led them to choose to evaluate their children based on new terms rather than just solely fact memorisation. It's one the rest of the world should surely follow.